The idea of the hero is something that even very small children understand at some level. Many perennially favorite picture books feature heroic characters (such as Max in Where the Wild Things Are — a retelling of Homer's Odyssey). As children grow, their exposure to different manifestations of the hero broadens. They encounter heroes in television, movies, books, magazines and music, and on the pages of their local newspapers.

The heroic archetype features prominently in literary analysis at the high school level. A clear understanding of, and the ability to manipulate and apply, this idea is critical to any approach to world literature for the high school student. Unlike most of the Mensa Foundation's lesson plans, this one includes the reading of a long novel as its culminating assignment.

This lesson plan was designed to tie into the Mensa Hero Bracket Challenge that began in the October 2010 issue of the Mensa Bulletin, with the results announced in the March 2011 issue. It is not necessary to read the article, however, for students to benefit from the lesson plan. If you are a member of Mensa, you (or your students) may read about the Hero Bracket Challenge in the October 2010 issue.

To begin your own heroic quest, read through the following information about the heroic archetype and how Luke Skywalker fits it!

Stanley Kunitz, former Poet Laureate of the United States, once said, "Old myths, old gods, old heroes have never died. They are only sleeping at the bottom of our mind, waiting for our call. We have need for them. They represent the wisdom of our race."

The idea of the hero is a theme in all media — books, music, art, even video games! American author Joseph Campbell is best known for his work with the myths of the world and how they connect us. Borrowing from James Joyce, he applied the term "monomyth" to refer to the pattern that myths around the world typically follow. His basic argument is that heroes in all cultures share a pattern that is predictable and recognizable.

A pattern that is followed by all or nearly all things of the same kind it is called an archetype, a concept developed by psychiatrist Carl Jung (the word comes from the Greek word for "model"). Campbell outlined the steps taken by heroes in virtually all cultures in his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces.

Other authors have modified Campbell's 17-step pattern, and that's what we'll do as well. We'll look at nine steps and find examples of them in movies, books and history. Keep in mind that heroes do not have to follow all of these (or Campbell's 17) steps in order to be a hero. You can be a hero and only experience some parts of the pattern. Once you become familiar with these ideas, you will see them everywhere.

So let's march a hero through the steps… How about Luke Skywalker? He's a good one to look at because the creator of Star Wars, George Lucas, deliberately modeled the story on classical mythology.

As you've seen, you will find examples of the heroic archetype in many places. One of these is art. Look at the image and answer the questions that accompany it.

If you want to read more about Hercules, read The Lernean Hydra.

Read the following quotes about heroes and respond to the questions.

Ralph Waldo Emerson once said, "A hero is no braver than an ordinary man, but he is brave five minutes longer." In what way is this true?

Can you think of an example in real life?

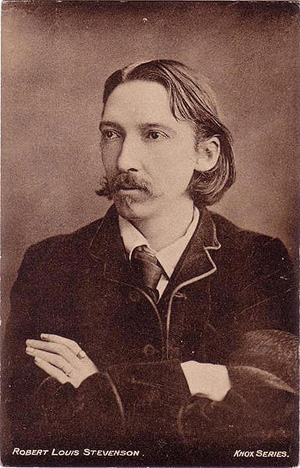

Robert Louis Stevenson said:

"The world has no room for cowards. We must all be ready somehow to toil, to suffer, to die. And yours is not the less noble because no drum beats before you when you go out into your daily battlefields, and no crowds shout about your coming when you return from your daily victory or defeat."

How is this similar to Emerson's idea?

Umberto Eco said, "The real hero is always a hero by mistake; he dreams of being an honest coward like everybody else." Do you think a reluctant hero is any less a hero than someone who embraces his/her heroic mission? Why or why not?

Now that you are familiar with the heroic journey, your own quest begins.

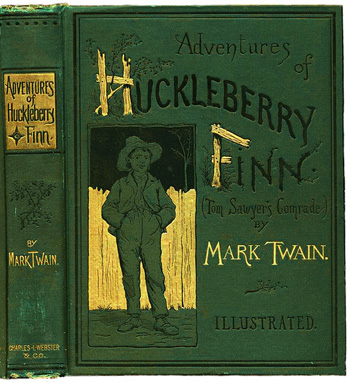

Read Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain. (Just one little line for such a big challenge!) Ernest Hemingway wrote of this novel, "It's the best book we've had. All American writing comes from that. There was nothing before. There has been nothing as good since." It's long and challenging, but it's worth it.

Where to find it

* It may be worthwhile to note that, while Amazon has scores of versions of this story available, reviewers report that some are abridged and not well marked as such. Surf with care!

Although we are focusing on the heroic archetype in the novel, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is a fairly complex novel to read, particularly if you are not used to novels written in dialect. If you need some guidance in reading the novel, here are some sources for you.

Trace Huck's path through the heroic archetype on the chart below. Remember that he may not have all of them, and some of them may be quite figurative (as opposed to literal). As you're reading, use sticky notes to mark places you see evidence of the heroic archetype.

After reading Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, write an essay in which you compare and contrast the heroic journeys of Luke Skywalker and Huck. In your essay, be sure to include the following ideas:

Your argument is only as strong as your evidence: Be as specific as possible in your use of examples. From the text, quote specific words and/or lines.

Know your goal: Make sure to look over the rubric below carefully so that you completely understand the level of expectation.

Show what you know: To adequately analyze the ideas, your essay's length should be about 1,000 words (three pages). Your spelling, syntax and grammar should be excellent so as not to distract from your ideas.

If you would like to challenge yourself even more, read The Lord of the Rings trilogy and march Frodo through the heroic archetype. Who do you think fits the pattern better, Frodo or Luke?

More reading

Watch it!

The American Film Institute ranked the top 50 film heroes of all time on a list. Watch some of the movies and think about whether the heroes in them match what you know about heroes.

This series of lessons was designed to meet the needs of gifted children for extension beyond the standard curriculum with the greatest ease of use for the educator. The lessons may be given to the students for individual self-guided work, or they may be taught in a classroom or a home-school setting. Assessment strategies and rubrics are included at the end of each section. The rubrics often include a column for "scholar points," which are invitations for students to extend their efforts beyond that which is required, incorporating creativity or higher level technical skills.